The State of New Mexico does have statutes in place to help preserve free-roaming horses with Colonial Spanish markers. Some of the horse rescue centers in the state are aware of and working to preserve Spanish Colonial horses removed from their historical home ranges. The Horse of the America’s registry does registry Colonial Spanish horses from New Mexico strains recognized by the Endangered Equine Alliance.

But those statutes do not protect New Mexican horses on Federal lands. The Forest Service manages approximately 7,100 wild horses and 900 wild burros on 53 wild horse and burro territories on approximately 2.5 million acres of National Forest System lands in 5 Forest Service regions, 19 national forests, and 9 states. Of these 53 territories, 34 are active and 19 are inactive. Of the 34 active territories, located in Arizona, California, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, and Utah, approximately 24 are jointly managed in cooperation with the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) wild horse and burro program.

One area managed by the Forest Service is the Caja del Rio. A mere eight miles from the city of Santa fe, this area is the northeastern end of the range that the foundation Colonial Spanish Medicine Paint stallion San Domingo came from. The Forest Service blurb for the Caja del Rio Grant horses now reads: ‘The herd history is not well known. The herd may be quite old since it is in close proximity to the earliest Spanish settlements and first source of horses. Wild horses have been known to frequent the Caja since at least 1934. After passage of the Wild Free-Roaming Horse and Burro Act of 1971, the Caja Wild Horse Territory was officially recognized and listed.

Many years back my Medicine Horse stallion, Apache, brought me the story of his lineage through Martin Prechtel, whose mother was a school teacher at Santo Domingo Pueblo. I had put up a poster of my Medicine Paint Apache at the feed-store and Martin came by to see the horses when he saw it. He knew about the horses because he had grown up hearing stories from the elders in the pueblo.

As I remember the tale, the Santo Domingo say that when Jesus (Spaniards) first showed up he was friendly and traded all sorts of goods with them. For many years it was a good relationship. He had new plants to share including wheat, grapes, peaches, and apples. He shared his animals, including chickens, pigs, goats, sheep, cattle, dogs, cats, and of course horses. He shared what he knew about weaving both wool and cotton, and working metal, and making leather. He married their daughters and established his village on the other side of the river. And he shared his ceremonies and spiritual practices.

Historians now agree that many of those who came to Northern New Mexico were fleeing persecution by the Catholic Spanish Crown, so their movements were not officially recorded. We now know that at least one breeding population of Colonial Spanish horses shares both the conformation and the genetic markers of the Maghreb Barbs still found in North Africa. The symbols found on the earliest gravestones in the many small reclusive communities include six pointed stars associated with Sephardic Jews, other heretical pre-Christian symbols like the five-petaled rose and Greek or equal armed crosses as well as the crescent moon associated with Islamic or Moorish traditions,.

The story adds that when more of Jesus’ people began to travel north, they became very unpleasant and demanding to the indigenous peoples. So the pueblos all got together and decided to chase him and his friends back down the direction they had come from. Eventually Jesus was allowed to return, but the Pueblos made sure Jesus knew his place. While he was allowed to restore his homes and his churches, the Santo Domingo and other Pueblos kept Jesus’ horses for themselves.

Historians call this episode the Pueblo Indian Revolt and the Peaceful Reconquest, but they rarely tell it from the Pueblo point of view. Since the Spanish bureaucracy had lengthy and strict rules regarding who could own and ride horses, indigenous peoples keeping Colonial Spanish horses was and is a profoundly revolutionary act. The herds of horses running on the Caja del Rio lands are spoils of war, a living sign of the Pueblo people’s resiliency and self-determination. Acknowledging the likely Colonial Spanish genetics of these horses would mean acknowledging the presence and activity of the Keres speaking indigenous and Hispanic peoples that arrived long before any Anglo-Americans.

The accuracy of the oral history of the Keres speaking pueblos is supported by anthropologists studying the dispersal of Colonial Spanish horses among indigenous peoples in North America. There is anthropological evidence of long-standing close ties between the Keres speaking pueblos like Santo Domingo and the Southern Athabascan speaking peoples we now know as the Apache and Navajo. Anthropological evidence also indicates that the Apache/Navajo peoples appear to be the first indigenous peoples to fully adapt their life styles to include Colonial Spanish horses. Herds of free-roaming Colonial Spanish horses are still found on Apache and Navajo reservation lands.

‘Herd origination may have come from early settlement in Santa Fe, La Cienega, Cieneguilla, and La Bajada. Blood lines from this source would have been of Spanish origin. Adjacent ranches and Pueblos could have been sources of quarter horse bloodlines. Rumors indicate that race track horses past prime have been released onto the territory for retirement. This may also be true of local recreational horses.’

The Forest Service claim that most of the horses are sorrels and bays of Quarter Horse type is not supported by recent photos . Eddie Moore’s photograph of a Square Horse from the Caja del Rio for the Albuquerque Journal proves differently. Below is a distinctively Square Colonial Spanish type horse roaming the Caja Del Rio in the Santa Fe National Forest west of Santa Fe in August 2021.

Hispanic oral history in Agua Fria also disagrees with the Forest Service. For hundreds of years, the Comancheros who wintered over in Agua Fria, ran the horses they brought with them to train and sell in the Caja del Rio. Since there was always fresh water at the San Isidro crossing of the Santa Fe River, they were able to catch the horses when they came to drink. The genetics of the descendants of those horses could open a window into the true history of this area.

The difference between the Hispanic Comancheros and the Uto-Aztecan speaking Comanche and Ute peoples is blurry at best. But at their peak the Comanche raided and traded horses north and east to the Missouri River, west to the Rocky Mountains and as far south as the Sierra Madre. Guanajato was home to wealthy Mexican horse breeders who imported quality breeding stock from the Old World until the Mexican War of Independence in 1810.

‘In 1975, 1978, and 1988, studies were conducted to obtain information on the herd. The 1975 study estimated a population of 55 horses; the 1978 study estimated a population of 37 horses; and the 1988 study estimated a population of 45 horses. From the date of herd designation, there have been neither herd reductions nor herd supplementation. There is only speculation to account for the relatively stable herd numbers: lion predation, illegal shooting and capture, or disease.‘

The Forest Service glosses over the fact that mountains lions are discriminating predators. They will select slow and injured adult horses to kill buut one of their very favorite meal is foals. When I was working as a wildfire dispatcher for the Bureau of Land Management one of my co-workers explained to me that they shot mountains lions on their ranch because the lions did not bother to hunt the wily, wiry, alert and agile Colonial Spanish foals when they could feast on slow dull meaty Quarter Horse colts.

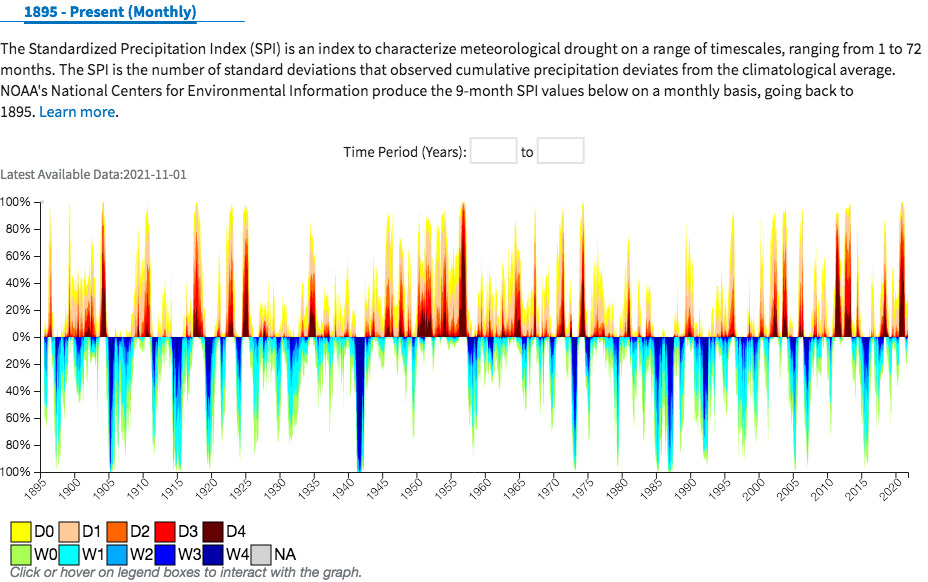

The Forest Service completely fails to mention starvation as a means of population control, although it is a common way for domestic horses to die in the harsh environment of the high desert. Most domestic horses released onto the desert die long before they are able to reproduce if they do not have access to supplemental feed. The Forest Service’s average rainfall is optimistic for drought years and low for wet years. As you can see by the chart below, this area has experienced rainfall extremes for as long as there are records.

‘The topography is composed of rolling hills and swales, dotted by cone like peaks. Elevations range from 5250 to 7315 feet. Temperatures range from 19° in the winter to 90°+ F in the summer. Average annual precipitation is 17 inches.’

After Adolph Bandelier, the Swiss-American anthropologist and explorer, who researched the cultures of the area and supported preservation of Bandelier National Monument first hiked this area in search of ruins he wrote that the territory was some of the roughest and most difficult he had ever encountered. That Colonial Spanish horses survive and reproduce under the harsh conditions of the high dry desert of the Caja del Rio is a testament to their unique hardiness. This area is currently threatened by development so please support the New Mexico Wildlife Federation’s effort to protect this extra-ordinary area and all its wild life, including these historic horses!

Pingback: Santa Fe & The Ghost Horses

Some words before I try the link one last time…. https://www.tarynokesson.com/2022/04/08/road-journal-santa-fe-and-the-ghost-horses/

LikeLike

The link works!

LikeLike

These horses are extremely shy and completely feral compared to other herds I’ve met (Salt River and Heber). I feel lucky to have seen the two I have. Thank you for the information.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, elusive is how they have managed to survive. I’d love to see pictures, if you happen to take any.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I did. I’ll link you when they are ready.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It dawned on me WordPress may be blocking me from posting the link?

LikeLike